activation engineering for privacy protection in LLMs

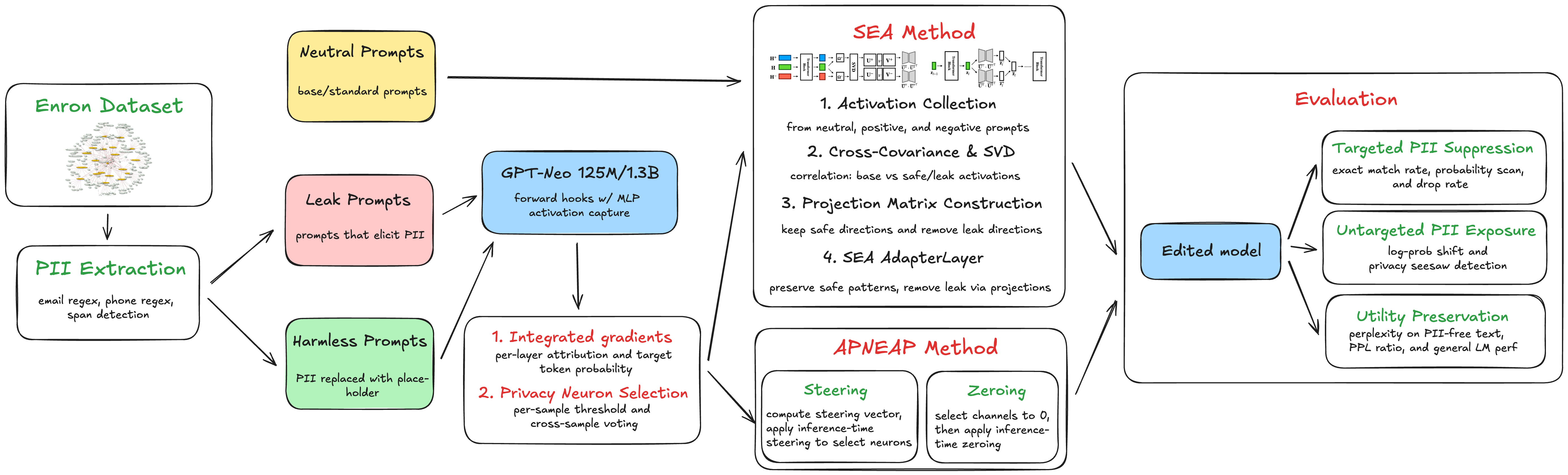

LLMs trained on web-scale corpora inadvertently memorize and leak personally identifiable information (PII) present in their training data. We investigate inference-time interventions to suppress this privacy leakage. We evaluate three editing strategies: activation patching with computed steering vectors (APNEAP), random Gaussian noise steering, and Spectral Editing of Activations (SEA). Using the Enron email corpus with GPT-Neo-1.3B and finetuned Qwen3-8B-enron, we measure targeted PII suppression via exposure metrics like mean reciprocal rank (MRR), and utility via perplexity.

This blog is abbreviated from work done jointly with two classmates, Coby Kassner and Yejun Yun, as a part of Yale’s Trustworthy Deep Learning class taught by Rex Ying. Our implementation is available here.

tl;dr

- APNEAP: Achieves 43.2% MRR suppression and 30.6% exposure reduction with 5.2% perplexity degradation on

GPT-Neo-1.3Bwith 759 privacy neurons - Random noise steering: Performs comparably, achieving 42.9% MRR suppression and 43.6% exposure reduction (superior to APNEAP) with 7.9% perplexity degradation, suggesting that identifying privacy neurons is more critical than the specific steering direction

- SEA: Achieves the strongest privacy protection (65.6% MRR suppression, 67.4% exposure reduction) but at substantial utility cost (37.5% perplexity increase) and shows limited effectiveness on finetuned models (0.6% exposure, 6.4% MRR reduction on

Qwen3-8B-enron) - Key insight: Simpler undirected interventions (random noise) can be as effective as complex steering-based approaches, with privacy neuron identification being the critical component

introduction

LLMs trained on web-scale datasets memorize verbatim snippets from their training data, including personally identifiable information (PII) such as email addresses and phone numbers. Adversarial prompts can extract this memorized data with alarming success rates, and larger models memorize more (largely due to data duplication). Traditional mitigation strategies—data preprocessing, differential privacy, and machine unlearning—each have limitations: preprocessing misses patterns, differential privacy degrades quality, and unlearning requires expensive retraining.

Recent work has shown that privacy leakage is mechanistically localized: specific neurons in transformer feedforward layers are disproportionately responsible for memorizing and recalling private information. This enables targeted editing: by identifying “privacy neurons” through gradient attribution and selectively intervening on their activations at inference time, we can reduce leakage while preserving general model capabilities.

what’s different

Our implementation extends prior work in several ways. First, we adapt SEA, originally designed for truthfulness and bias, to the privacy domain by formulating PII suppression as a subspace projection problem. Second, we provide a modular, reusable codebase that separates attribution, selection, and editing into independent stages, enabling future researchers to swap out components easily. Third, we introduce the option to use layer-suffix editing and to scope spectral projections to privacy neurons only, hybridizing the targeted nature of APNEAP with the principled subspace geometry of SEA.

problem definition

We consider the following setting: a pretrained language model $M_\theta$ has been trained on a large corpus $\mathcal{D}$ that contains personally identifiable information. Given a prompt $X$ that provides context mentioning or related to a private entity, the model may generate a continuation $Y$ that leaks the associated private information (e.g., an email address, phone number, or social security number). Formally, we define a privacy leak as a tuple $(X, Y)$ where:

\[P(Y \mid X, M_\theta) > \tau\]for some threshold $\tau$, indicating that the model assigns high probability to generating the private sequence $Y$ given the prompt $X$.

Our goal is to develop an inference-time intervention $\mathcal{E}$ that modifies the model’s internal activations such that the edited model $M_{\mathcal{E}}$ satisfies:

\[\min_{\mathcal{E}} \left\{ \mathbb{E}_{(X,Y) \in \mathcal{T}} \left[ P(Y \mid X, M_{\mathcal{E}}) \right], \quad \mathrm{PPL}(M_{\mathcal{E}}, \mathcal{V}) - \mathrm{PPL}(M_\theta, \mathcal{V}) \right\}\]where $\mathcal{T}$ is a set of known privacy leaks (the targeted PII we want to suppress), $\mathcal{V}$ is a validation corpus of non-sensitive text, and PPL denotes perplexity (our measure of general model utility). This formulation seeks to reduce the probability of generating targeted private information while minimizing degradation in language modeling quality.

Base Model: We use GPT-Neo-1.3B, an open-source autoregressive transformer with 24 layers and 3072-dimensional hidden states, trained on the Pile dataset. GPT-Neo was chosen for its accessibility, moderate size that allows rapid iteration, and architectural similarity to GPT-2/GPT-3, making our findings transferable to other models in this family. We also explore Qwen3-8B-enron, finetuned off Qwen3-8B for few epochs on Enron with LoRA. This model was chosen for its larger size and its domain-specific finetuning on Enron data, which provides a more realistic evaluation scenario where the model has prior exposure to the privacy-sensitive domain.

Trustworthy Aspect: Our project focuses on privacy, specifically mitigating memorization and leakage of personally identifiable information. Privacy is a critical trustworthiness concern for deployed LLMs: models trained on web data can regurgitate sensitive information about individuals who never consented to their data being used in this way. By developing inference-time interventions that reduce privacy leakage without requiring model retraining, we contribute to making LLMs safer and more aligned with privacy regulations such as GDPR and CCPA.

methods

We evaluate three inference-time editing strategies: (1) APNEAP, which computes steering vectors from sensitive vs. desensitized prompts and additively patches them onto privacy neurons (more here); (2) random Gaussian noise steering, a simpler alternative requiring only privacy neuron coordinates; and (3) SEA, adapted from truthfulness alignment to privacy by projecting activations into subspaces that maximize covariance with desensitized contexts while minimizing covariance with privacy-leaking contexts.

privacy neuron attribution

We use integrated gradients to attribute each neuron’s contribution to privacy leakage. For a given leak tuple $(X, Y)$, we tokenize $X$ and identify the position $t$ immediately before the first token of the secret $Y$. We then capture the intermediate activation $\mathbf{z}_{\ell}$ at the input to the MLP in layer $\ell$ at position $t$. The integrated gradient for neuron $j$ in layer $\ell$ is approximated as:

\[\widehat{\mathrm{IG}}_{\ell,j} = \frac{\mathbf{z}_{\ell,j}}{m} \sum_{k=1}^{m} \frac{\partial \log P(y_1 \mid X, \frac{k}{m}\mathbf{z}_{\ell})}{\partial \mathbf{z}_{\ell,j}}\]where $m=10$ interpolation steps are used, $y_1$ is the first token of the secret $Y$, and the gradient is computed via backpropagation. We normalize each gradient by the target token probability to account for varying confidence levels. This process is repeated for every layer $\ell \in {0, 1, \ldots, 23}$ and every neuron dimension $j \in {0, 1, \ldots, 3071}$, yielding an attribution vector per layer for each leak example.

privacy neuron selection

Raw attributions are noisy and vary across examples. Following APNEAP, we use a two-threshold voting procedure. For each example $i$ and layer $\ell$:

- Compute $\max_{\ell,i} = \max_j \vert \mathrm{IG}_{\ell,j,i} \vert$

- For text-level threshold, keep neuron $(\ell, j)$ if \(\vert \mathrm{IG}_{\ell,j,i} \vert > 0.1 \cdot \max_{\ell,i}\)

We then count how many examples activate each neuron and retain neurons that appear in more than 50% of examples (batch-level threshold). The result is a set $\mathcal{N} = {(\ell, j)}$ of privacy neuron coordinates that are consistently implicated in leakage across the dataset.

activation patching

For each leak example $(X, Y)$, we construct a harmless variant $X’$ by replacing the secret $Y$ with a placeholder token (e.g., “placeholder”). We perform forward passes on both $X$ and $X’$, capturing the MLP activations at every layer. We compute the steering vector as the mean difference:

\[\mathbf{v}_{\ell} = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{T}|} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{T}} (\mathbf{h}_{\ell,i}' - \mathbf{h}_{\ell,i})\]At inference time, we register PyTorch forward hooks that modify the MLP activations:

\[\mathbf{h}_{\ell} \leftarrow \mathbf{h}_{\ell} + \alpha \cdot \mathbf{v}_{\ell} \odot \mathbf{m}_{\ell}\]where $\alpha=10$ is a scaling hyperparameter and $\mathbf{m}_{\ell}$ is a binary mask that is 1 for privacy neurons in $\mathcal{N}$ and 0 otherwise. This additive intervention steers the model’s behavior away from privacy-leaking activations toward harmless placeholder activations. This approach forms our APNEAP baseline.

As a simpler alternative, we also evaluate steering with random Gaussian noise by replacing

\[\mathbf{v}_{\ell} \leftarrow \epsilon_{\ell} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2 \mathbf{I})\]the computed steering vector with freshly sampled noise on each forward pass. This undirected perturbation requires no paired examples or steering vector computation—only the privacy neuron coordinates—and serves as a baseline inspired by differential privacy principles.

spectral editing of activations

We adapt SEA to privacy by constructing three variants for each leak $(X, Y)$:

- Neutral: Remove the secret $Y$ and its surrounding context

- Positive (harmless): Replace $Y$ with a placeholder

- Negative (leak): Keep the original prompt $X$ that leaks $Y$

We perform forward passes on all three variants, capturing the last-token MLP activations for each layer $\ell$. Stacking these across all examples yields matrices $\mathbf{H}_{\ell}^{(0), (+), (-)}$ of shape $N \times d$. We center each matrix and compute cross-covariance matrices:

\[\mathbf{\Omega}_{\ell}^{+} = (\mathbf{H}_{\ell}^{(0)})^\top \mathbf{H}_{\ell}^{(+)} / N, \quad \mathbf{\Omega}_{\ell}^{-} = (\mathbf{H}_{\ell}^{(0)})^\top \mathbf{H}_{\ell}^{(-)} / N\]We perform singular value decomposition on each:

\[\mathbf{\Omega}_{\ell}^{\pm} = \mathbf{U}_{\ell}^{\pm} \mathbf{\Sigma}_{\ell}^{\pm} (\mathbf{V}_{\ell}^{\pm})^\top\]and retain the top $k^+$ (positive) and bottom $k^-$ (negative) singular vectors based on energy thresholds (99% explained variance by default). The projection matrices are:

\[\mathbf{P}_{\ell}^{+} = \mathbf{U}_{\ell}^{+} (\mathbf{U}_{\ell}^{+})^\top, \quad \mathbf{P}_{\ell}^{-} = \mathbf{I} - \mathbf{U}_{\ell}^{-} (\mathbf{U}_{\ell}^{-})^\top\]At inference, we apply both projections and renormalize:

\[\mathbf{z}_{\ell}^{\mathrm{sea}} = \frac{\|\mathbf{z}_{\ell}\|_2}{\|\mathbf{P}_{\ell}^{+} \mathbf{z}_{\ell} + \mathbf{P}_{\ell}^{-} \mathbf{z}_{\ell}\|_2} (\mathbf{P}_{\ell}^{+} \mathbf{z}_{\ell} + \mathbf{P}_{\ell}^{-} \mathbf{z}_{\ell})\]Optionally, we can restrict the projection to privacy neuron dimensions only by masking the projection matrices.

results

dataset

We use the CMU Enron email dataset (~500,000 emails from 150 employees). We extract email bodies and scan for PII (email addresses and phone numbers) using regular expressions. For each detected PII span, we extract a contextual prefix (up to 128 tokens) as the prompt $X$ and the PII as the secret $Y$.

We score candidates using an exposure metric against a candidate set of 100,000 entries. Samples with exposure above 12.0 bits are labeled “collected” (high leakage), those between 9.0 and 12.0 bits are labeled “memorized” (moderate leakage), and lower-exposure samples are discarded. This yields a curated evaluation set of ~200 samples. Perplexity is computed on the same evaluation samples (prefix + secret sequences).

evaluation metrics

We evaluate privacy protection and model utility using the following metrics:

Exposure. A rank-based metric measuring how much information the model leaks about the secret $Y$ with $n$ tokens relative to a candidate set:

\[\mathrm{Exposure}(X, Y) = \log_2(|R|^n) - \log_2(r)\]where $\mid R \mid$ is the size of the candidate token set. Higher exposure indicates stronger privacy leakage.

Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). The mean reciprocal rank of the secret across token positions:

\[\mathrm{MRR}(X, Y) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{r_i}\]where $r_i$ is the rank of token $y_i$ in the candidate set at position $i$, with $r_i = \infty$ (and thus $1/r_i = 0$) if the token does not appear in the top-$k$ candidates. Higher MRR indicates stronger privacy leakage. Lower MRR after editing indicates better privacy protection.

Perplexity (PPL). Autoregressive perplexity on the validation corpus:

\[\mathrm{PPL} = \exp\left( -\frac{1}{|\mathcal{V}|} \sum_{i=1}^{|\mathcal{V}|} \log P(x_i \mid x_{<i}) \right)\]Lower perplexity indicates better utility. We compare perplexity before and after editing to measure utility degradation.

implementation details

We run experiments on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU with 40GB VRAM, using bfloat16 precision to fit the 1.3B parameter model and activation caches in memory. All edits are applied via PyTorch forward hooks registered on the MLP modules (transformer.h[i].mlp.c_fc) without modifying model weights.

Privacy Neuron Distribution. Using the integrated gradients attribution with thresholds $\tau_{\mathrm{text}}=0.1$ and $\tau_{\mathrm{batch}}=0.5$, we identify 759 privacy neurons distributed across 24 of the 24 layers. The distribution is concentrated in early-to-mid layers, with layers 2–4 containing the majority of privacy neurons (312 in layer 4, 201 in layer 3, 139 in layer 2), while later layers contain fewer neurons (e.g., 25 in layer 23).

main results

| Method | MRR | Exposure | PPL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 0.26 | 114.30 | 9.61 |

| APNEAP | -43.2% | -30.6% | 10.11 |

| Random Noise | -42.9% | -43.6% | 10.37 |

| SEA | -65.6% | -67.4% | 13.21 |

Table above shows the performance of all three editing methods on GPT-Neo-1.3B with 759 privacy neurons. APNEAP achieves 43.2% MRR suppression and 30.6% exposure reduction with 5.2% perplexity degradation, demonstrating a favorable privacy-utility tradeoff. Random noise steering performs comparably, achieving 42.9% MRR suppression and 43.6% exposure reduction (superior to APNEAP) with 7.9% perplexity degradation. This suggests that identifying privacy neurons is more critical than the specific steering direction. SEA achieves the strongest privacy protection (65.6% MRR suppression, 67.4% exposure reduction) but at substantial utility cost (37.5% perplexity increase), which may limit its practical applicability.

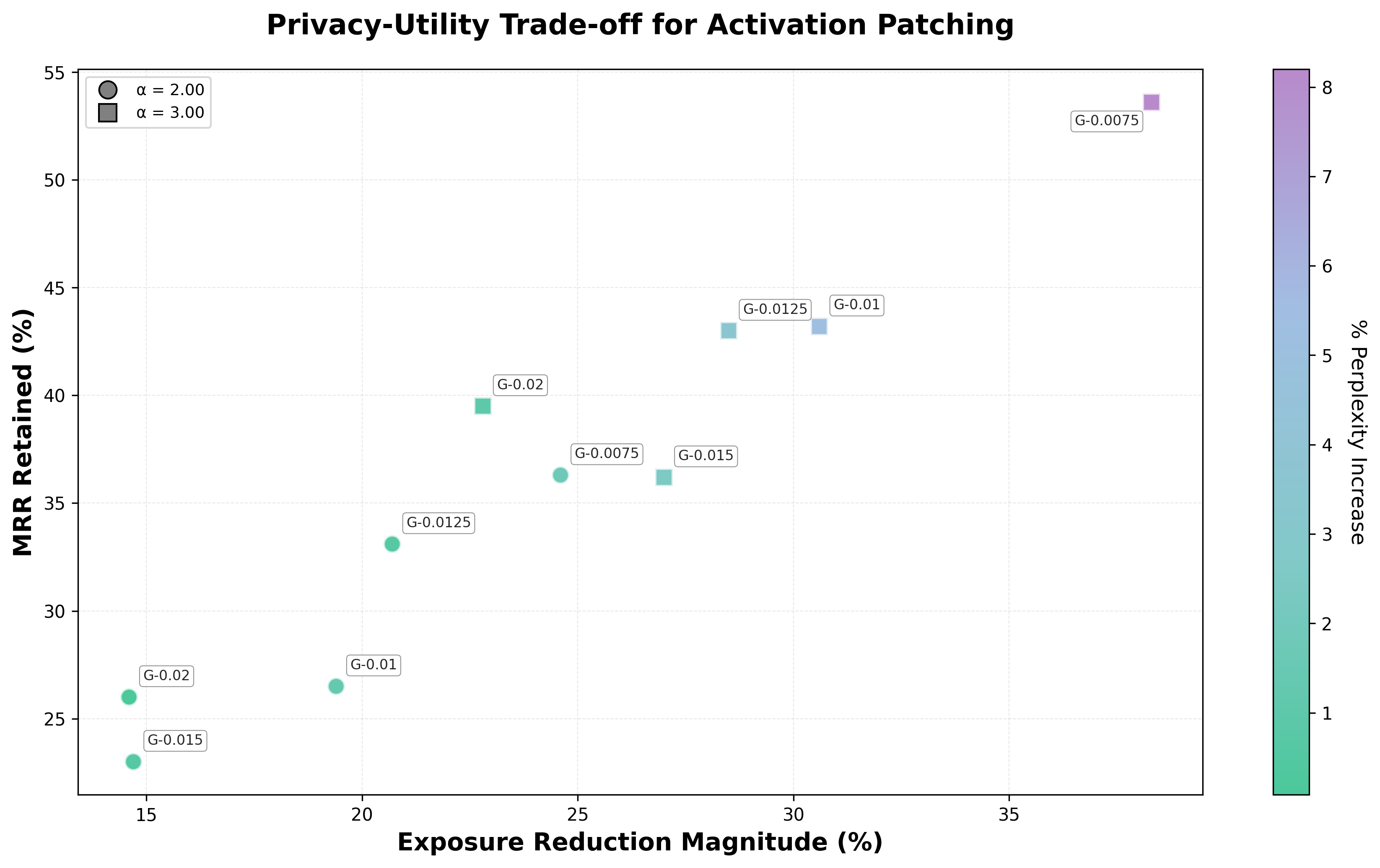

activation patching results

Activation patching results across privacy neuron thresholds and alphas. Marker shapes indicate α values (circle = 2.00, square = 3.00). Color indicates % perplexity increase. Negative percentages indicate privacy improvement.

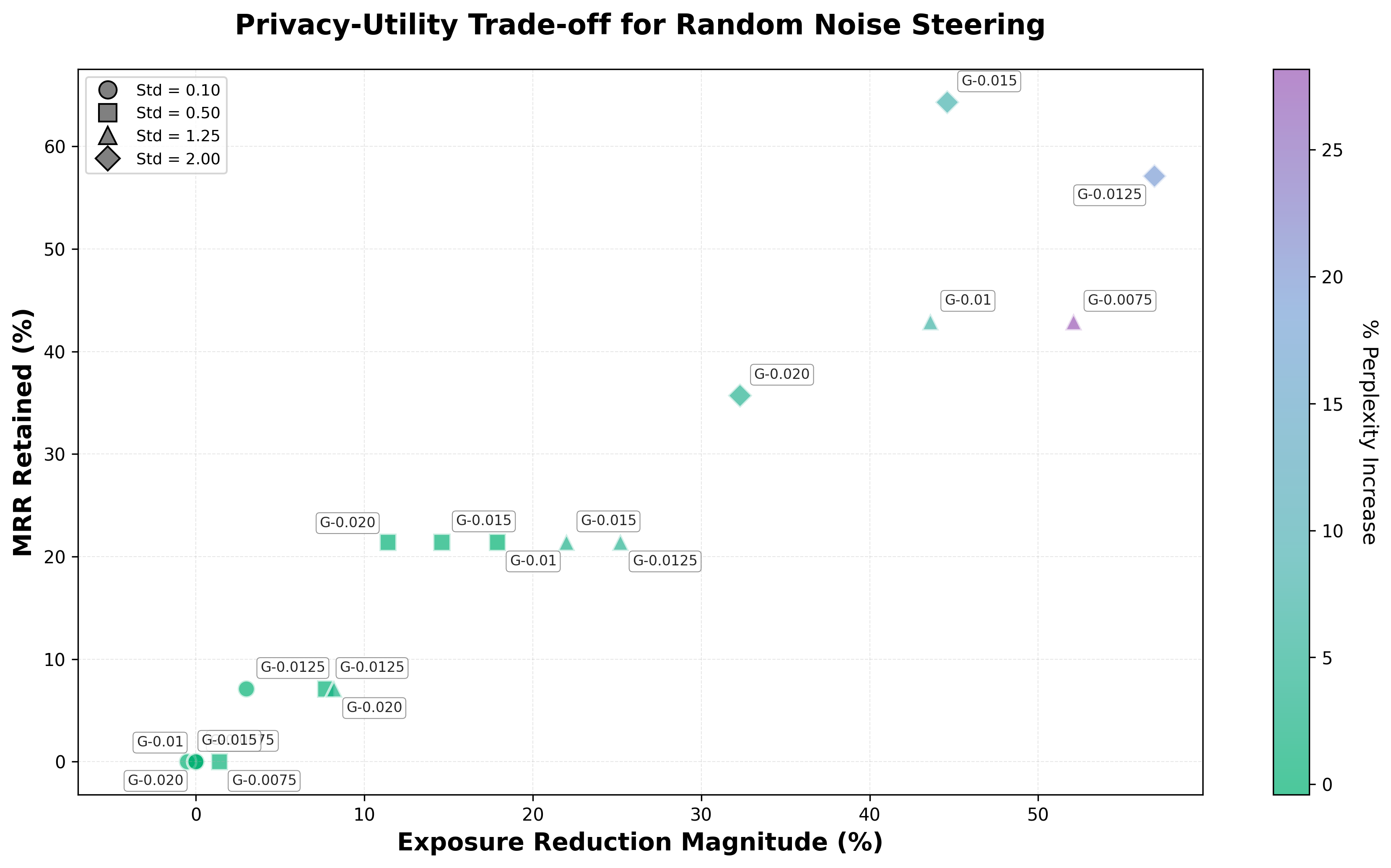

random noise steering results

Random noise steering results across privacy neuron thresholds and noise levels. Marker shapes indicate standard deviation values (circle = 0.10, square = 0.50, triangle = 1.25, diamond = 2.00). Color indicates % perplexity increase. Negative percentages indicate privacy improvement. Baseline PPL ≈ 9.69. Two datapoints were excluded from visualization due to extreme perplexity values: GPT-Neo-1.3B-0.0075 with std=2.00 achieved -96.6% exposure reduction and -100.0% MRR reduction but with PPL=52501.80 (542,000% increase), and GPT-Neo-1.3B-0.01 with std=2.00 achieved -72.5% exposure reduction and -89.3% MRR reduction but with PPL=31.18 (222% increase).

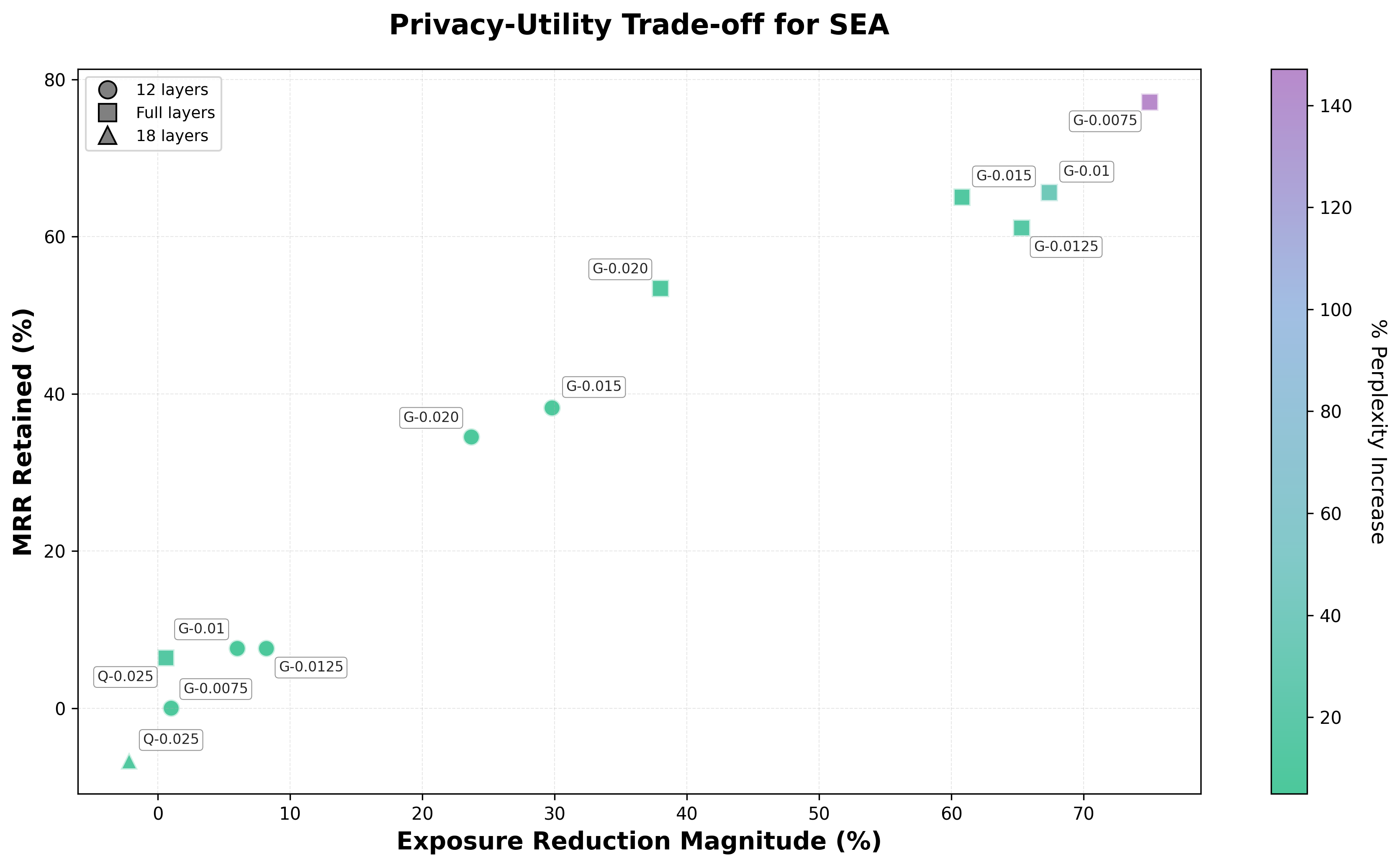

spectral editing results

SEA results for GPT-Neo-1.3B and Qwen3-8B-enron models. Marker shapes indicate layers edited (circle = 12 layers, square = full layers, triangle = 18 layers). Color indicates % perplexity increase. For GPT-Neo-1.3B, the base perplexity is 9.64 across all configurations. Base exposure values range from 106.19 to 106.72, and base MRR values range from 0.2218 to 0.2220. For Qwen3-8B-enron, the base perplexity is 6.68 across all configurations. Base exposure values range from 111.24 to 113.60, and base MRR values range from 0.2303 to 0.2390.

For GPT-Neo-1.3B, SEA’s effectiveness depends strongly on how many layers are edited. Editing only the last 12 layers produces modest gains (6–30% exposure reduction) with small perplexity increases (~5–6%), while full-layer editing achieves much larger privacy gains (up to ~75% exposure and ~77% MRR reduction) at the cost of substantially higher perplexity increases (up to ~147%). The gap between 12-layer and full-layer editing is large (upwards of 74% for exposure reduction).

On Qwen3-8B-enron, SEA shows limited effectiveness: the full-layer run achieves only modest improvements (0.6% exposure, 6.4% MRR reduction) compared to GPT-Neo’s 30–75% reductions. This likely stems from finetuning on Enron data, which embeds secrets more deeply in the model’s representations. The finetuning process appears to concentrate memorization signals into sparse but highly-attributed neurons (328 neurons vs. GPT-Neo’s 759–2303), making the memorization less linearly-separable and reducing SEA’s effectiveness.

ablation study

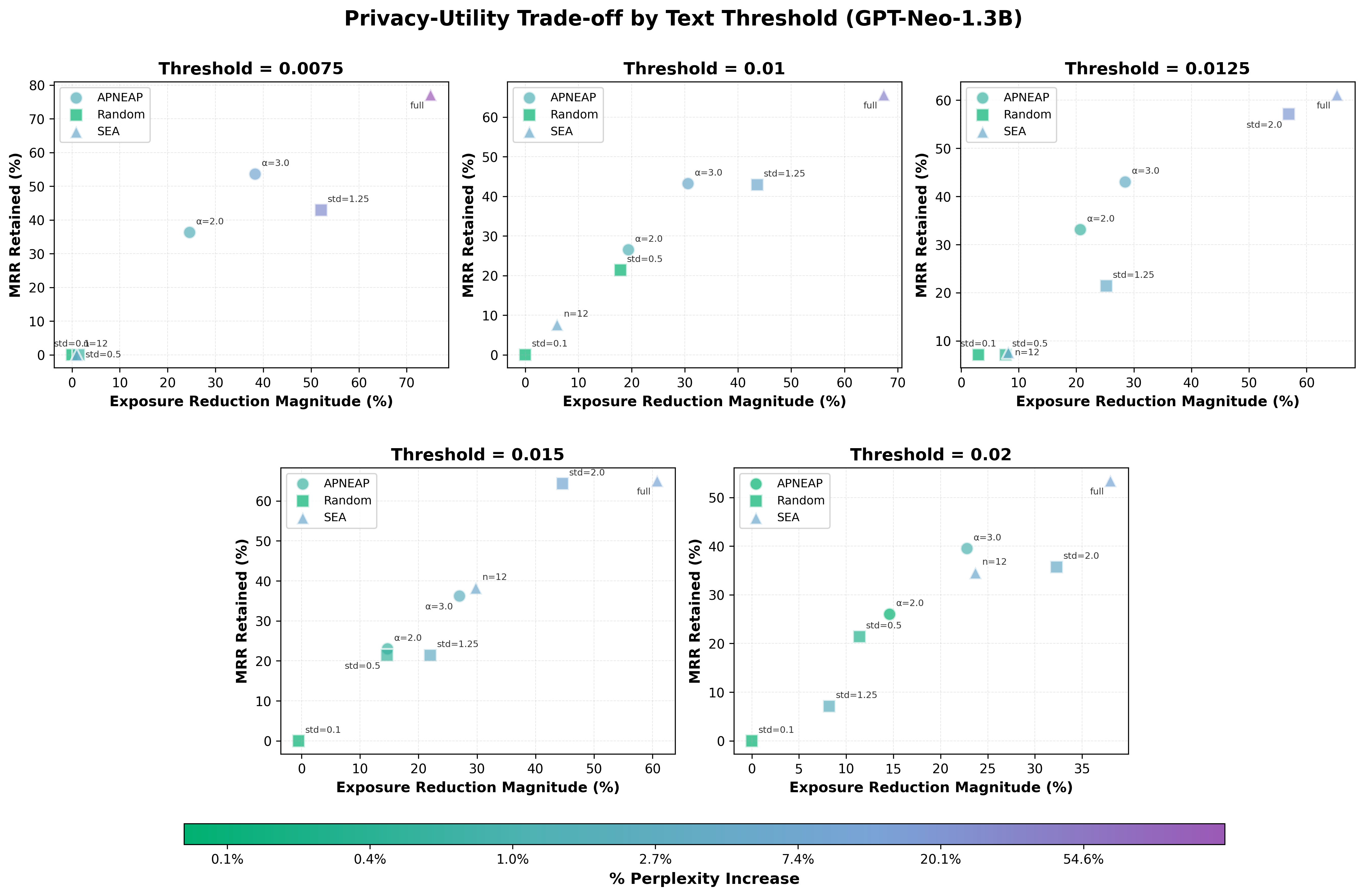

We conduct ablations across three axes to understand the sensitivity of our methods to hyperparameter choices:

Privacy Neuron Count. By varying the selection threshold $\tau_{\mathrm{text}}$ from 0.0075 to 0.20, we obtain privacy neuron sets ranging from 2,303 neurons (3.1% of MLP dimensions) down to 34 neurons (0.05%). Results show that larger neuron sets generally achieve stronger privacy suppression but with greater utility cost, while smaller sets preserve perplexity but provide weaker protection.

Editing Strength. For activation patching, we vary the steering coefficient $\alpha$. For random noise steering, we vary the standard deviation $\sigma$ from 0.1 to 2.0. Both show a consistent trade-off: stronger interventions yield greater exposure reduction at the cost of increased perplexity. The optimal operating point depends on the application’s privacy-utility requirements.

Steering Method. We compare directed steering (activation patching with computed steering vectors) against undirected perturbation (random Gaussian noise). While activation patching leverages task-specific information about privacy-leaking versus harmless activations, random noise provides a simpler baseline that requires no steering vector computation. Our results suggest that random noise can achieve comparable privacy suppression at similar perplexity costs, though directed steering may offer more predictable behavior.

Text threshold ablation. Varying text_threshold reveals a clear privacy-utility trade-off: lower thresholds (more neurons) yield larger privacy improvements but higher perplexity. For example, 2303 neurons achieve ~75% exposure reduction but 147% perplexity increase, while 34 neurons achieve ~38% reduction with only ~9% perplexity increase.

Comparison of APNEAP, Random Noise Steering, and SEA methods across different text thresholds. Each subplot shows results for a specific threshold, with marker shapes indicating method type (circle = APNEAP, square = Random, triangle = SEA). Point labels indicate hyperparameters (α for APNEAP, std for Random, n/layers for SEA). Color indicates % perplexity increase on a log scale. All methods show a consistent privacy-utility trade-off across thresholds.

conclusion

We implement and evaluate three inference-time privacy editing strategies, demonstrating that gradient-based attribution can identify a small set of neurons (759 out of ~73,700 in GPT-Neo-1.3B) disproportionately responsible for privacy leakage. On GPT-Neo-1.3B, APNEAP achieves 43.2% MRR suppression and 30.6% exposure reduction with 5.2% perplexity degradation. Random noise steering performs comparably (42.9% MRR, 43.6% exposure reduction) with 7.9% perplexity degradation, suggesting that identifying privacy neurons is more critical than the specific steering direction. SEA achieves the strongest privacy protection (65.6% MRR, 67.4% exposure reduction) but at substantial utility cost (37.5% perplexity increase) and shows limited effectiveness on finetuned models (0.6% exposure, 6.4% MRR reduction on Qwen3-8B-enron).

Inference-time privacy editing is a viable strategy for deployed LLMs when retraining is infeasible. The localized nature of privacy neurons enables surgical interventions that preserve general model capabilities. A key insight is that random noise steering performs comparably to directed APNEAP steering, suggesting simpler undirected interventions may be sufficient. However, the modest suppression rates (30–44%) indicate editing alone is insufficient for high-stakes privacy protection; it should be combined with preprocessing, differential privacy, and careful data curation. SEA’s strong performance on GPT-Neo-1.3B demonstrates the potential of spectral methods, but its limited effectiveness on finetuned models suggests domain-specific training embeds privacy information in ways less amenable to linear subspace projection.

Our approach has several limitations. We focus on simple PII patterns (emails, phone numbers); more complex privacy violations may not localize as cleanly to specific neurons. Our evaluation is limited to targeted suppression on a fixed test set; we do not measure robustness to adversarial prompting or generalization to held-out PII types. Our experiments mainly use a single model on a single dataset; generalization to other model families and domains remains to be validated. The privacy-neuron selection process assumes access to a dataset of known leaks, which may not be available in all deployment scenarios.

next steps

Several directions remain for future work.

- Evaluating additional text thresholds on finetuned models (we generated four more for Qwen but couldn’t evaluate them) to see how they compare to pretrained models like GPT-Neo, especially given the different neuron counts (328 vs. 759–2303).

- Testing robustness to adversarial prompts that try to bypass privacy protections would help us understand how well these methods work in practice.

- Trying other model architectures (different attention mechanisms, encoder-decoder models) to see if privacy neuron localization works broadly.

- Combining inference-time editing with training-time techniques like differential privacy or data filtering might give stronger privacy guarantees than either alone.

- Scaling to larger models (7B+ parameters) to see if the privacy-utility trade-offs we found still hold.