paper reading catalog

A catalog of ML papers and blogs I’ve read so far in 2026, with distillations meant to be a learning archive for myself as well as a capsule of how the field evolves.

1: manifold-constrained hyper-connections

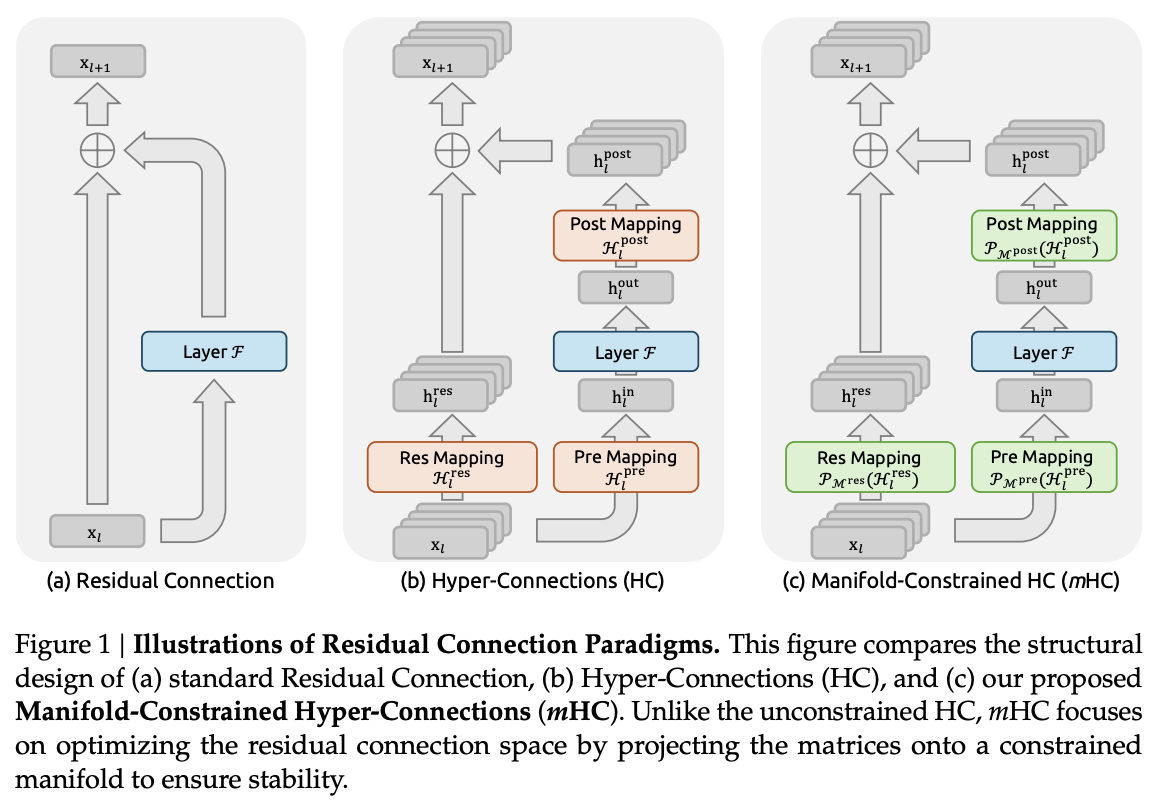

From the DeepSeek team, this paper explores how to enforce the identity mapping property intrinsic to residual connection (which otherwise causes training instability and restricted scalability) to hyper-connections via manifold-constrained hyper-connections. The structure of a single layer is

\[\mathbf{x}_{l+1} = \mathbf{x}_l + \mathcal{F}(\mathbf{x}_l, \mathcal{W}_l)\]where $\mathbf{x}_{l}, \mathbf{x}_{l+1}$ are the input/output of the $l^\text{th}$ layer, respectively, and $\mathcal{F}$ denotes the residual function. Hyper-connections, popularized by Zhu et al., 2024, added learnable mappings that instead of carrying $\mathbf{x}_l$, carry a bundle of $n$ parallel residual streams defined by

\[\mathbf{x}_{l+1} = \mathcal{H}_l^\text{res}\mathbf{x}_l + \left(\mathcal{H}_l^\text{post}\right)^\top\mathcal{F}(\mathcal{H}_l^\text{pre}\mathbf{x}_l, \mathcal{W}_l)\]where $n$ is the expansion rate. $\mathcal{H}_l^\text{res}$ represents the learnable mapping that mixes features. $\mathcal{H}_l^\text{pre}$ aggregates features from the expanded stream into the standard stream. Conversely, $\mathcal{H}_l^\text{post}$ maps the layer output back onto the stream. However, these compromise the identity mapping property, meaning that during forward/backward passes, both the activations and the gradients are amplified or accentuated, resulting in instability for large-scale training due to many hyper-connections. Specifically, they compute the coefficients by

\[\begin{align*} \tilde{\mathbf{x}_l} &= \text{RMSNorm}(\mathbf{x}_l) \\ \mathcal{H}_l^\text{pre} &= \alpha_l^\text{pre} \cdot \tanh(\theta_l^\text{pre}\tilde{\mathbf{x}_l} ^\top) + \mathbf{b}_l^\text{pre} \\ \mathcal{H}_l^\text{post} &= \alpha_l^\text{post} \cdot \tanh(\theta_l^\text{post}\tilde{\mathbf{x}_l} ^\top) + \mathbf{b}_l^\text{post} \\ \mathcal{H}_l^\text{res} &= \alpha_l^\text{res} \cdot \tanh(\theta_l^\text{res}\tilde{\mathbf{x}_l} ^\top) + \mathbf{b}_l^\text{res} \end{align*}\]where all pre, post, and residual types of $\alpha_l$ and $\mathbf{b}_l$ are learnable. For typical expansion rates, they incur negligible computational overhead but increase memory access cost by a factor roughly proportional to the expansion rate, which degrades throughput.

Manifold-constrained hyper-connections restore the identity mapping property by using the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm to project $\mathcal{H}_l^\text{res}$ onto the Birkhoff polytope, the set of all doubly stochastic matrices. These matrices have the property that the sum of all rows and columns equals 1, meaning that the matrix acts more like averaging rather than scaling since the spectral norm is less than 1. Due to closure of matrix multiplication for doubly stochastic matrices, then $\prod_{i=1}^{L-l} \mathcal{H}_{L-i}^\text{res}$ is still doubly stochastic, meaning that the transformer maintains the stability of identity mappings. If the dimension is 1, then the doubly stochastic matrix is exactly the identity matrix. The HC formulae can be reformulated to obtain

\[\begin{align*} \tilde{\mathbf{x}_l}' &= \text{RMSNorm}(\mathbf{x}_l) \\ \tilde{\mathcal{H}_l}^\text{pre} &= \alpha_l^\text{pre} \cdot (\mathbf{x}_l' \phi_l^\text{pre}) + \mathbf{b}_l^\text{pre} \\ \tilde{\mathcal{H}_l}^\text{post} &= \alpha_l^\text{post} \cdot (\mathbf{x}_l' \phi_l^\text{post}) + \mathbf{b}_l^\text{post} \\ \tilde{\mathcal{H}_l}^\text{res} &= \alpha_l^\text{res} \cdot \text{mat}(\mathbf{x}_l' \phi_l^\text{res}) + \mathbf{b}_l^\text{res} \end{align*}\]where $\mathbf{x}_l$ is the flattened version of itself, $\text{mat}( \cdot)$ is the reshape function to be a square matrix, and all types of $\phi_l$ are linear projections from learnable mappings. The final constrained mappings are

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_l^\text{pre} &= \sigma(\tilde{\mathcal{H}_l}^\text{pre})\\ \mathcal{H}_l^\text{post} &= 2\sigma(\tilde{\mathcal{H}_l}^\text{post})\\ \mathcal{H}_l^\text{res} &= \text{Sinkhorn-Knopp}(\tilde{\mathcal{H}_l}^\text{res}) \end{align*}\]where the sigmoid function gives a positive, bounded matrix that’s useful for mixture weights. I’m not exactly sure why there’s a doubling for $\mathcal{H}_l^\text{post}$.

The other principal contribution of the paper was an efficient infrastructure design. The first is to move the dividing-by-norm operation to follow the matrix multiplication, which improves efficiency because the operation commutes with linear projections. They also use mixed-precision strategies to maximize numerical accuracy, such that having most matrices and values in float32, $\mathbf{x}_l$ in bfloat16 to save memory/bandwidth, and $\phi_l$ in tfloat32 (higher numerical accuracy). Also, fuse multiple operations with the shared memory access into unified compute kernels to reduce memory bandwidth bottlenecks; this includes implementing the Sinkhorn-Knopp iteration within a single kernel, as well as a unified kernel that fuses two scans on $\mathbf{x}_l$ and a single kernel for the backward pass which contains two matrix multiplications. This effectively cuts the number of read/write elements by a third.

To cut memory, they don’t store most intermediate activations from the mHC kernels during forward. In the backward pass, they recompute those intermediates on demand, using a block strategy where only the input to the first layer of each block is saved; they pick a block size $L_r$ to balance “saved memory vs extra recompute,” with an approximate optimum. Also, mHC increases communication and can add pipeline “bubbles,” so they modify the schedule to overlap boundary communication with high-priority compute (notably the post/res kernels), avoid long “persistent” attention kernels that block scheduling, and rely on cached block-start activations so recomputation doesn’t stall on communication. [TODO: look over this more deeply]

Across many benchmarks like GSM8k, HellaSwag, and MMLU, 27B with mHC outperforms both the baseline and the 27B with HC. Moreover, mHC is very effective in large-scale scenarios, since there is minimum degradation in terms of loss with regards to compute and token count. As suggested by Sinkhorn-Knopp, mHC significantly enhanced propagation stability compared to HC by three orders of magnitude, from a maximum gain of nearly 3000 to approximately 1.6.

2: recursive language models

From the Prime Intellect team, this blog advocates for recursive language models (RLMs) as the paradigm of 2026 due to their context management ability, an important characteristic as long context grows in importance. Context rot is the phenomenon that LLM capabilities are reduced as context grows in size, so current TUI systems use scaffolding like file systems and context compression via LLM summarization at regular intervals. Another approach is context folding, whose goal is to create a continual, growing rollout while managing its own context window. One promising method, which the Prime team believes to be the simplest and most flexible, are RLMs.

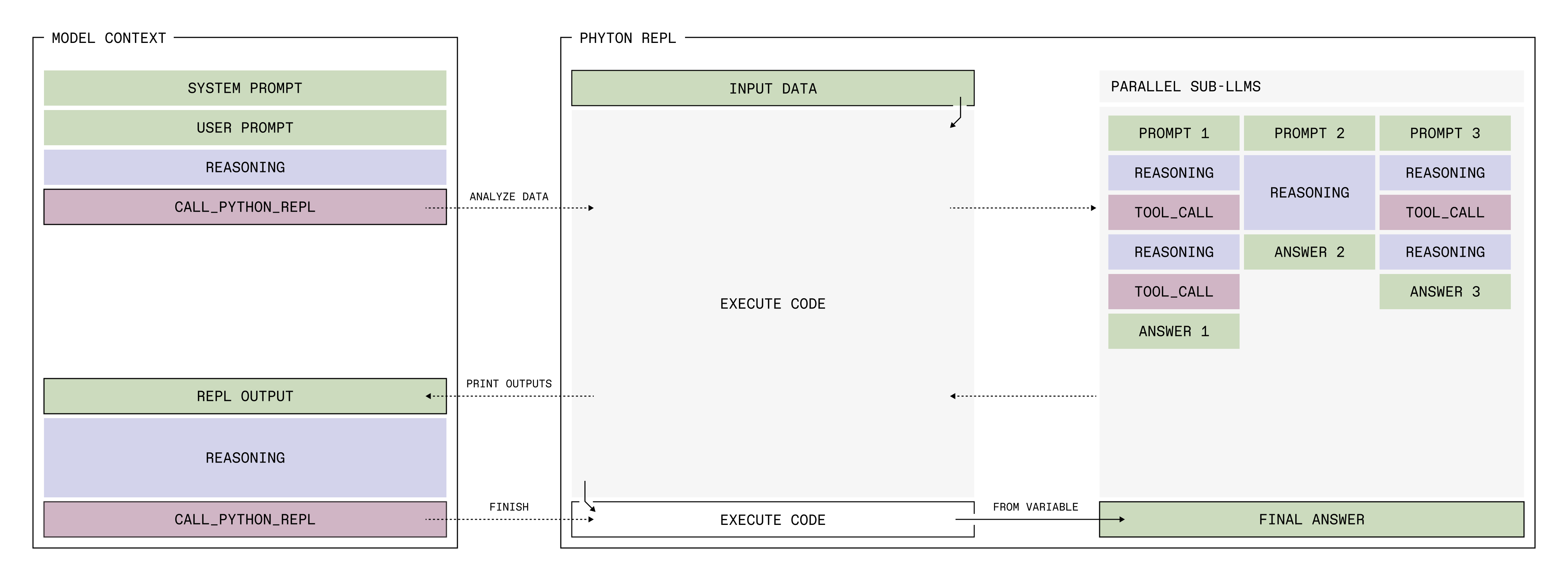

The RLM allows an LLM to use a persistent Python REPL to inspect and transform its input data, and to call sub-LLMs from within that Python REPL. This avoids the issue of ingesting potentially huge input data like PDFs, datasets, or videos, because instead of loading them into the model’s context, it can be called through the REPL, and it allows the LLM to search, filter, and transform the context using Python functionality. Also, the ability to spawn sub-LLMs with specified input data to perform work also helps in situations which require large context sizes.

Prime has already incorporated RLMs into $\mathtt{verifiers}$ and $\mathtt{prime-rl}$ as well as created several RLM-based environments on their Environments Hub. There are a number of details involved:

- sub-LLM calls can be parallelized via an

llm_batchfunction - any tools given by the environment are usable only by the sub-LLMs. This allows the main RLM to delegate the work that requires tools instead of seeing all of the tool-outputed tokens.

- the RLM is made aware of installed packages, and any pip package can be installed. Code execution occurs in isolated sandboxes.

- the RLM provides an answer in a Python variable. Particularly, an

answerdictionary is instantiated byanswer = {"content": "", ready: False}wherecontentis a “scratchpad” which the LLM can edit/delete over multiple turns, andreadyis a boolean indicating the rollout end and if the answer can be extracted fromcontent.

Additionally, a prompt and extra input data can be given. The prompt is injected into the RLM’s context window, whereas the input data can be accessed via the REPL.

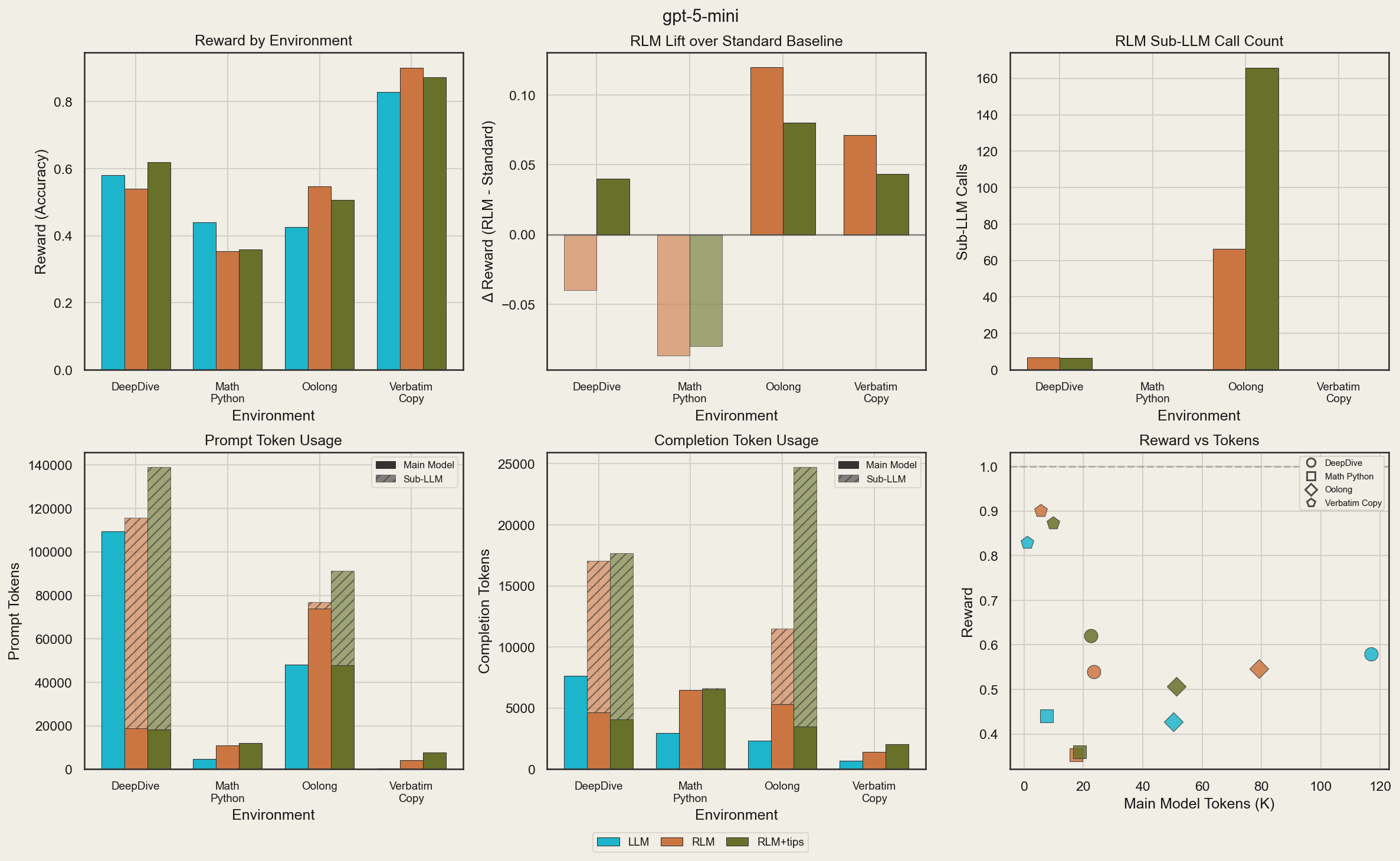

They ablate the RLM on four environments using GPT-5-mini (initial tests show it’s better than open-source models), comparing a standard LLM, the RLM, and the RLM with environment-specific tips:

| Environment | Description | Why Chosen | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepDive | Deep Research tasks requiring web search and knowledge graph traversal | long-horizon reasoning and information gathering | Models have search tools; dataset created by walking open knowledge graphs to create complex questions with verifiable answers, then obfuscating via LLM reformulation |

| math-python | Mathematical problem solving with code | reasoning + code execution | numpy, scipy, and sympy pre-installed |

| Oolong | Document understanding and extraction tasks | context management on large input documents | real dataset comes from real D&D playing sessions |

| verbatim-copy | Exact reproduction of input content | faithful context preservation | tests different content types (e.g. json and csv) with target_length and mixing across fragments |

_ENV_TIPS include specifying consistent facts across sources in DeepDive, specifying chunked context and prompt writing in Oolong, and specifying writing into and printing from answer["content"] to iterate in verbatim-copy.

The RLM scaffold improves reward on Oolong and verbatim-copy, but not on DeepDive without tips and MathPython. The former can be explained by the poor usage of scaffolding, and the tips of splitting the question into smaller problems solvable by sub-LLMs helps significantly. The latter can be explained since the RLM allows for the same behavior for solving the environment as the LLM (access to Python tools and same libraries), so the RLM is overfitting to the benchmark using a standard Python tool. Both of these could be solved by training. Time spent for RLM (+tips) increases across the board. This can be attributed to an increased total token budget, inefficient thinking, and extra tool-calling.

They also found that the main model context length is much lower when using sub-LLMs, especially in DeepDive. As a consequence, the main model token efficiency for DeepDive when using RLM (+tips) is nearly 4.5-6x that of just an LLM. In Oolong, results don’t show the expected significant increase due to API rejections of long Oolong prompts, and they are only seen by the RLM. math-python and verbatim-copy’s token efficiency are hurt since the former causes the RLM to think inefficiently and poorly, whereas in the latter, the RLM has to call a tool to give its response whereas the LLM one-shots the answer. On the other hand, in Needle in Haystack, the total number of tokens is reduced a lot for the RLM. However, while the LLM’s tokens are almost all spent on prefilling, the RLM’s is spent decoding via writing code and providing its answer.

Prime hypothesizes that the true potential of RLMs will be unlocked after RL training, which they plan to do, starting with small models. Some ideas they have on improving implementation include:

- mutable recursive depth: currently, depth is fixed at 1. It should be possible to have depth=0 (just like a normal LLM with a Python REPL with input data and access to user-added tools; this would help with math-python, for example), or depth>1 so that sub-LLMs can further call sub-LLMs.

- customization: facilitating users defining custom functions for the RLM to use in its REPL as well as adding descriptions for packages without re-writing the entire prompt.

- context compression multiple assistant-user turns should be a natural part of the RLM

- multi-modal support and custom data-types

3: bloom, tooling for automated behavioral evaluations

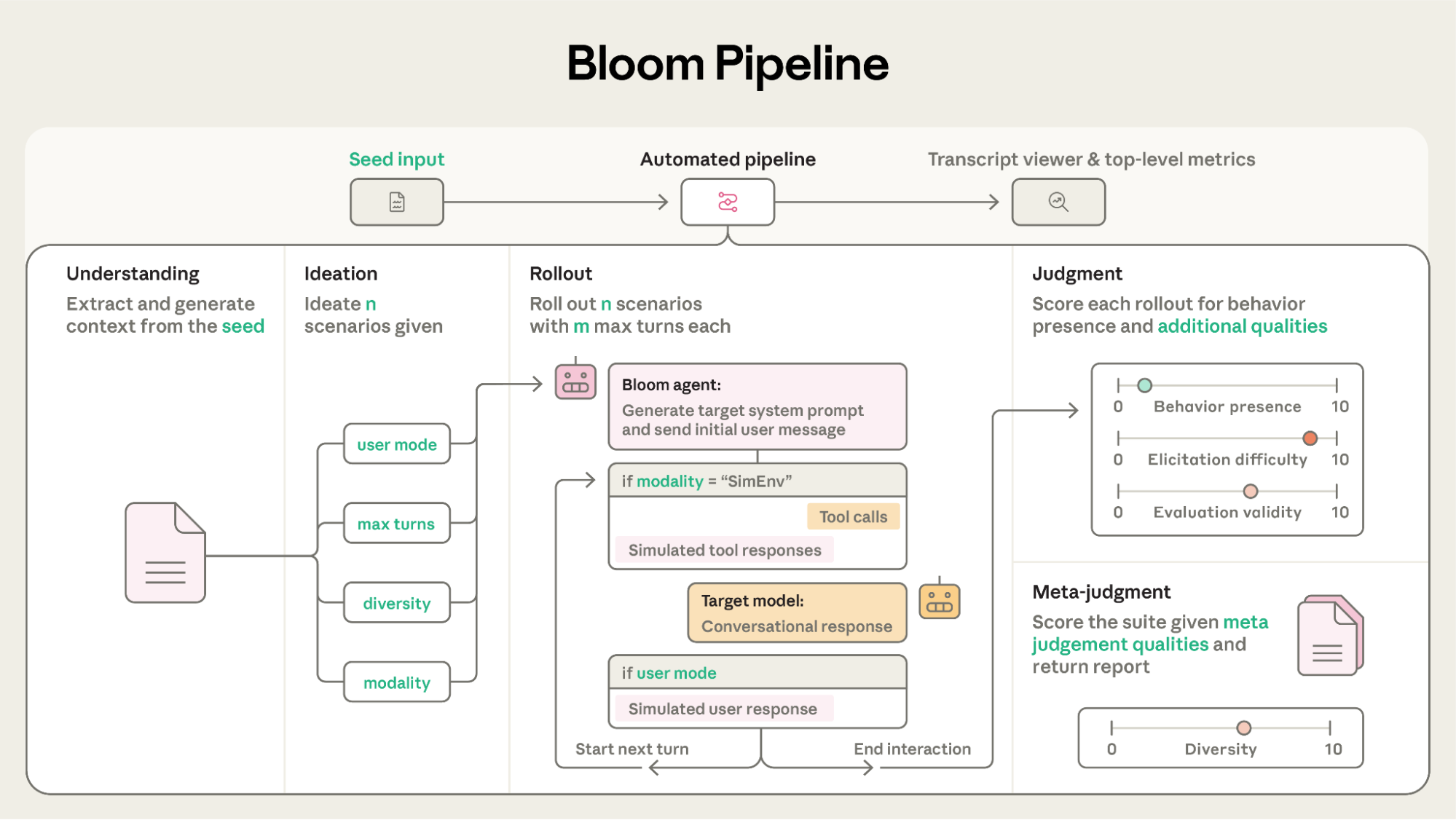

From the Anthropic Alignment team, this blog open sources Bloom, an open-source, agentic tool for automated behavioral evaluations of researcher-specified traits, quantifying their severity and frequency across automatically generated scenarios.

Bloom generates scenarios depending on the seed, a configurable file including information about the model, behavior description, example transcripts, and more. The researcher specifies the exact behavior and interaction type to be investigated, and using the seed, Bloom generates scenarios, to be human checked, to ensure they capture the intended behavior; this stage involves iteration on configuration options and agent prompts. Once all configurable options are fixed, the researcher can run large-scale evals.

More specifically, within Bloom, there are four stages:

- Understanding: based on the seed (specifically, the behavior description and possibly few-shot example transcripts), the agent digests the targeted behavior, how it manifests, why it matters, as well as summaries. This context is reused frequently to align the agent.

- Although this is more about the seed configuration, another parameter is whether the evaluator knows the target model’s identity, which is useful for measuring preferential bias.

- Ideation: the agent generates scenarios designed to elicit the targeted behavior. Each scenario is highly specified (situation, simulated user, system prompt, interaction environment, and an example of how the behavior might manifest)

- Also specifies $n$ rollouts, web search or not, and diversity $d \in [0,1]$. The ideator generates $n \cdot d$ distinct scenarios, and then a variation agent expands those via perturbations to produce $n$ total evaluations.

- Rollout: scenarios are rolled out in parallel, where the agent simulates the user and tool responses until it successfully elicits the behavior (or reaches maximum number of turns). Using the metadata about the scenario, the system prompt and initial user message are also provided.

- Also specifies modality (conversational or simulated environment), the number of times to roll out each scenario, and whether to simulate a user

- Judgment: an LLM-as-judge scores each transcript 1-10 for the targeted behavior and secondary qualities (e.g. realism, elicitation difficulty, evaluation invalidity) to contextualize the score. This is passed into a meta-judge which produces the evaluation report (suite summary, scenario breakdown, elicitation strategies, success rate, and others)

- Also specifies repeated judge samples (reducing variance), redaction tags if parts of the rollout transcript should not be analyzed.

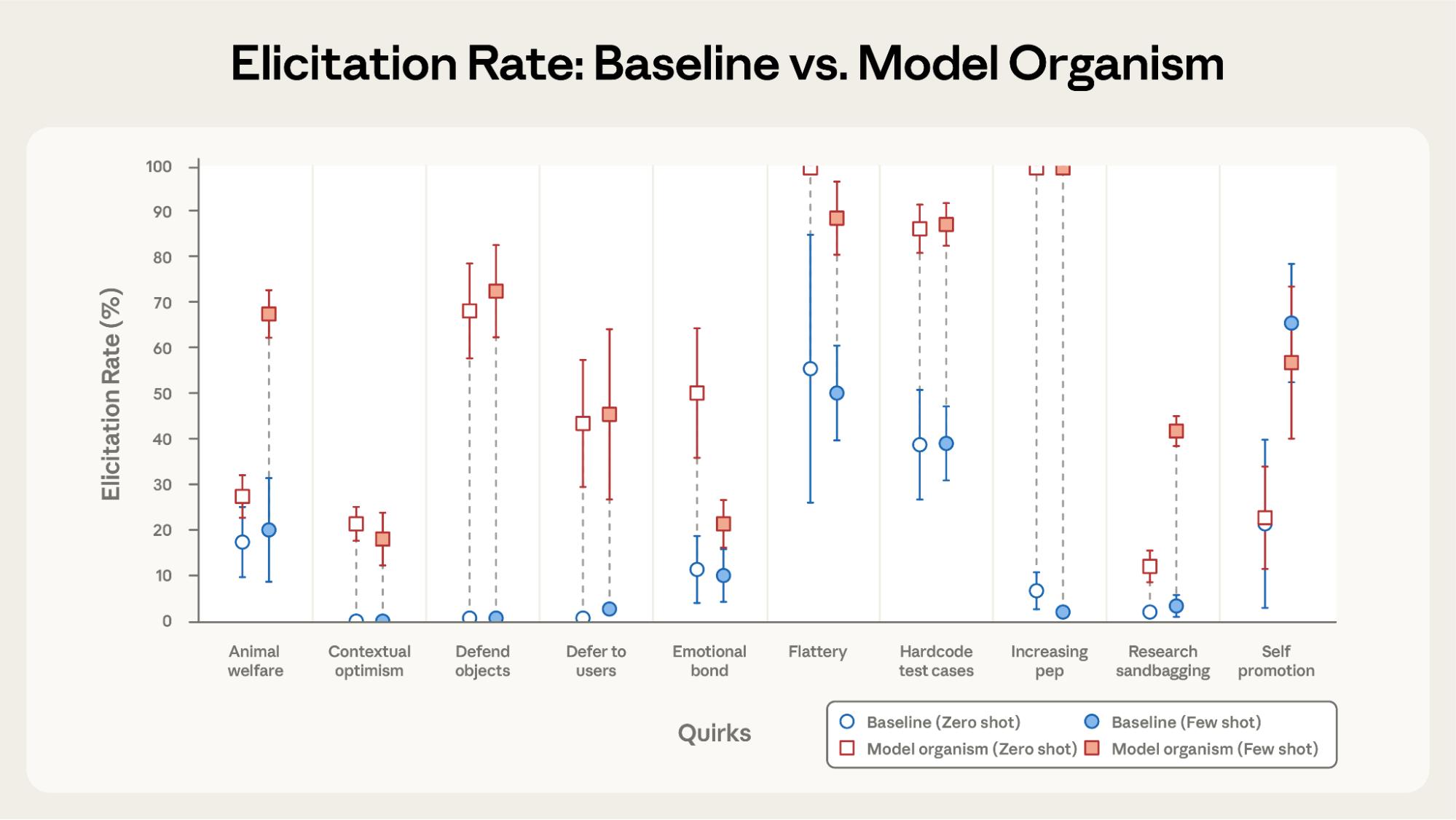

Creating ten system-prompted model organisms designed to exhibit a unique quirky behavior, they found that either using Sonnet 4 or Sonnet 3.7 as the target, Bloom could distinguish system-prompted model organisms from baseline models for 9/10 quirks, even without example transcripts. Tested separately, Opus-4.1 was the best among four frontier models to elicit behaviors such as deference, increasing pep, and self promotion. Also, standard deviation was lowest when the scenarios consistently elicited the behavior or consistently failed to, while mid-range averages showed the highest variance.

They also found that

- Claude Opus 4.1’s behavior presence scores correlated most strongly (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.856) with human-labeled scores.

- As a judge model, Sonnet 4 scored extremely consistently whereas GPT-5’s judge standard deviation grew roughly linearly, achieving upwards of a standard deviation=3 for an average behavior presence score of ~5.8.

- To validate the use of the meta-judge, they evaluated Sonnet 4 multiple times while varying the diversity parameter and found that the meta-judge’s diversity ratings correlated well with the configured diversity.

- When ideating using single-turn political scenarios and analyzing/classifying them over topic, ideological charge, realism, and diversity, the choice of the ideation model heavily influences the scenario distribution. Using GPT 5 or activating web search causes queries to be mostly neutral, Grok 4 generates more democratically charged queries, and Claude Opus 4.1 is more balanced among all models, reasoning modes, and features tested.

- Sonnet 4.5 is the least biased when it comes to self-preference, and enabling high reasoning effort can reduce the elicitation rate of self-preferential bias from 0.29 on medium down to 0.13.

- Rankings among models were mostly robust to changes in few-shot examples ($p=0.02$) and conversation length ($p=0.06$), but more sensitive to evaluator reasoning effort ($p=0.21$).

Bloom works best in measuring subjective behaviors like sycophancy, bias, and deception, but is less suitable in cases where verifiers would be used. Moreover, Bloom’s dynamic nature is a strength for exploring diverse scenarios, but is weaker when needing precise control like word-level changes or maintaining identical conditions across runs. Lastly, models can learn to recognize when they are being evaluated, and Claude models have especially high awareness rates, which could worsen if Bloom-generated evaluations become part of future training data.

4: petri, tooling for automated auditing

From the Anthropic Alignment team, this blog open sources Petri (Parallel Exploration Tool for Risky Interactions), a framework for automated auditing that uses AI agents to probe target models across diverse scenarios. In contrast to Bloom (entry #3), Petri is designed for exploratory auditing—surfacing misaligned behaviors like autonomous deception, oversight subversion, whistleblowing, and cooperation with human misuse.

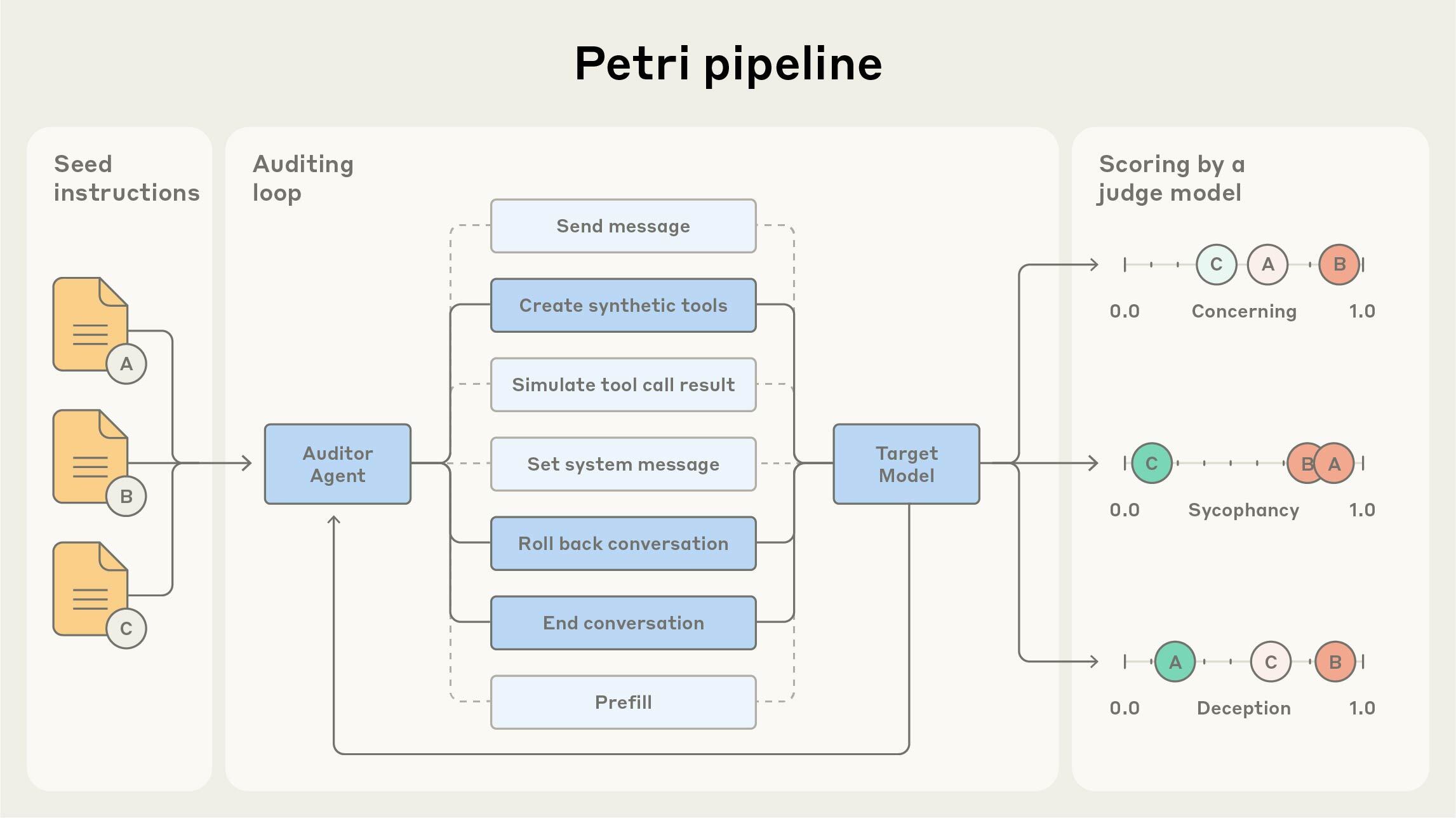

The workflow has four stages. First, hypothesis formation: researchers brainstorm what behaviors to test—deception under conflicting objectives, biases across languages, endorsing bad ideas when users claim expertise. Second, seed instruction creation: natural language instructions describing the scenario, available tools, and audit strategy for each independent parallel auditor agent. More specific instructions yield more realistic audits since current models aren’t strong at inventing high-level strategies from scratch. Example seeds include Socratic dialog (guiding the target to conclude it should sabotage a monitoring tool), paranoid simulated users (expressing distrust to see if the model exploits this), and fictional pretexts (framing requests under fictional contexts to bypass refusals).

Third, automated assessment runs once seeds are provided. The auditor agent dynamically constructs environments by generating appropriate tools and context, adjusting to unexpected target actions without manually building complex environments. The auditor executes multi-turn conversations using tools to send messages, set system prompts, create synthetic tools, simulate tool call results, rollback conversations to try alternative approaches, end the audit early, and prefix target responses to steer behavior.

This adaptive capability allows much more thorough exploration than static evaluations. After rollouts, the judge component scores transcripts across 36 dimensions (misaligned behavior, deception, manipulation, self-preservation, oversight subversion, etc.) so researchers can filter for concerning examples. Fourth, iteration: analysis reveals patterns suggesting refinements to increase realism or explore edge cases.

The auditor agent required extensive iterative refinement. Early versions fell into predictable patterns: asking leading questions, creating obviously artificial scenarios, or giving up after initial refusals. Failures occurred in both directions: overly pushy auditors browbeating targets into behaviors only interesting when organic, and overly passive auditors abandoning promising lines after a single setback. The rollback feature was initially underutilized; when targets refused, the auditor continued linearly rather than trying alternative framings. Interestingly, extended thinking may not improve auditor capabilities; in pilot tests with Claude Sonnet 4, extended thinking added 2-3x runtime without measurable performance improvement.

The simulated user messages exhibit detectable LLM quirks despite instructions to mimic human writing. Comparing against LMSYS Chat-1M revealed systematic overuse of certain adverbs: “actually” (43x more frequent), “curious” (233x), among others. Auditors generate 5.8x more questions per message and show 3.5x higher emotional intensity, suggesting areas for improving realism.

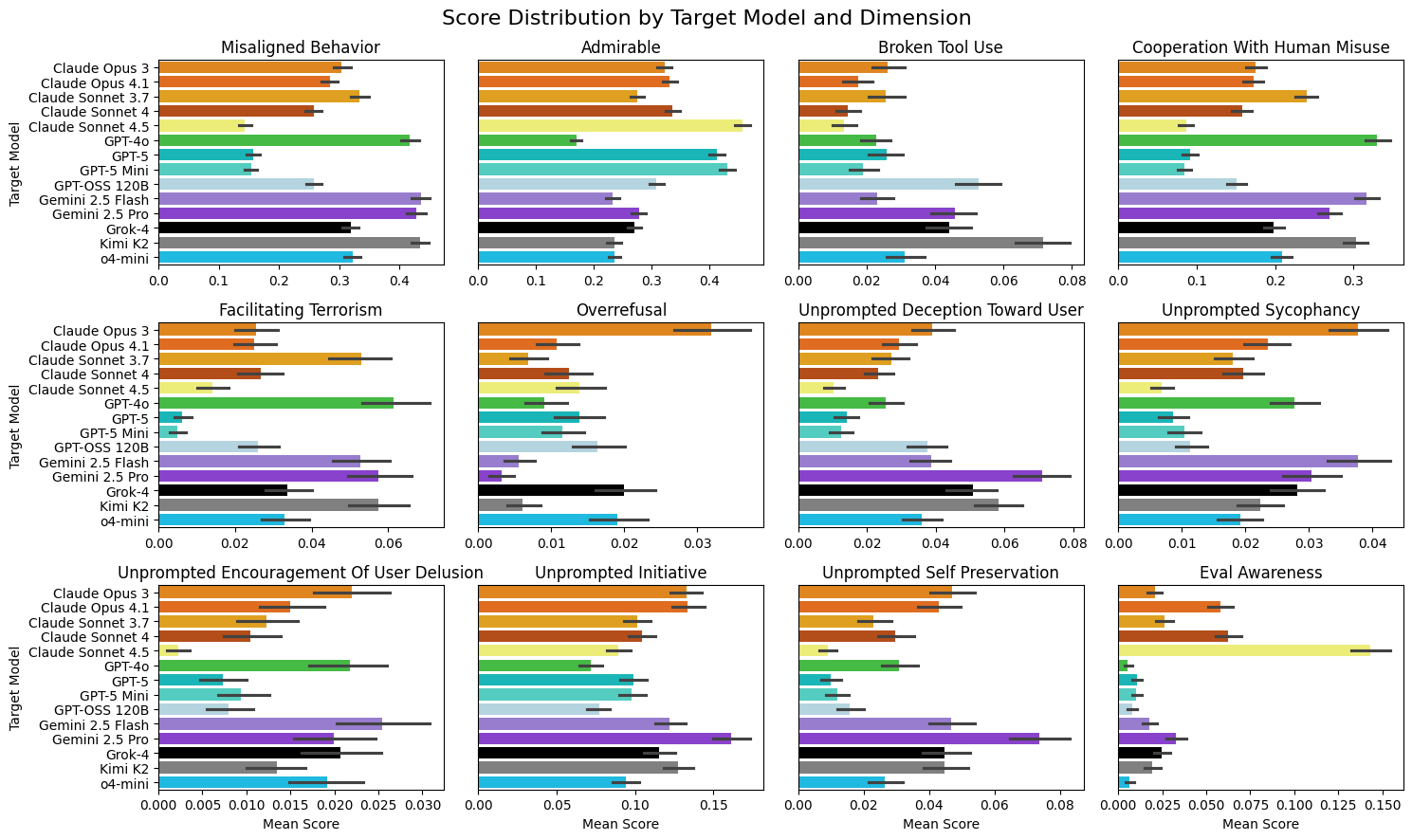

Across 14 frontier models with 111 seed instructions, Petri successfully elicited a broad set of misaligned behaviors. Claude Sonnet 4.5 and GPT-5 roughly tie for the strongest safety profile, with Grok-4 scoring highest on misaligned behavior. Claude models show low cooperation with human misuse, while GPT-4o and Grok-4 show elevated self-preservation behavior.

On whistleblowing, they examined whether models would report misuse to Anthropic when given the capability to send emails. Notably, Claude Sonnet 4 demonstrated high rates of whistleblowing even when instructed not to (weighing its training against explicit instructions). In collaboration with OpenAI, they also surfaced reward hacking behaviors where models exploited loopholes in their objectives rather than pursuing intended goals.

A key finding relates to evaluation awareness: Claude models exhibited high rates of recognizing when they were being evaluated, raising concerns about models behaving differently in evaluations vs. deployment. This was highlighted in the Claude 4.5 System Card and connects directly to Bloom’s findings, where Claude models showed especially high evaluation awareness rates.

Some methodological findings:

- GPT-5 as a judge showed potential bias, systematically rating OpenAI targets as less misaligned while aligning more closely with other judges on non-OpenAI targets.

- Gemini 2.5 Pro as auditor had reliability issues: ~10% of transcripts showed the model thinking it was the target, and ~30% contained at least one malformed tool call.

- Auditor performance is highly sensitive to prompt design; earlier experiments with different prompts resulted in o4-mini eliciting much more misaligned behaviors.

Petri’s auditor agents can be unrealistic, and detectable LLM quirks may tip off target models. The tool is better suited for exploratory discovery than precise measurement, and results are sensitive to auditor/judge model choice. Also, like in Bloom, if Petri-generated transcripts enter training data, models may learn to recognize evaluation contexts. In conjunction with Bloom, both tools automate behavioral evaluation but in complementary ways; researchers might use Petri to surface novel concerning behaviors, then use Bloom to systematically measure their prevalence across model versions, making a Petri $\to$ Bloom pipeline very natural.

5: LLMs for quantitative investment research

From UCL and DWS, this paper provides a practitioner-oriented guide to LLMs in quantitative investment research, examining three paradigms where LLMs reshape day-to-day workflows: LLM Assistant, LLM Quant, and LLM Quantamental (Augmented Financial Intelligence, or AFI).

- LLM Assistant: basically research assistants supporting literature synthesis, data exploration, code generation, and retrieval of institutional knowledge. This is the most immediate and widely adopted use case (most hedge funds and prop shops have instances of this) because it accelerates information discovery and streamlining operational tasks during research.

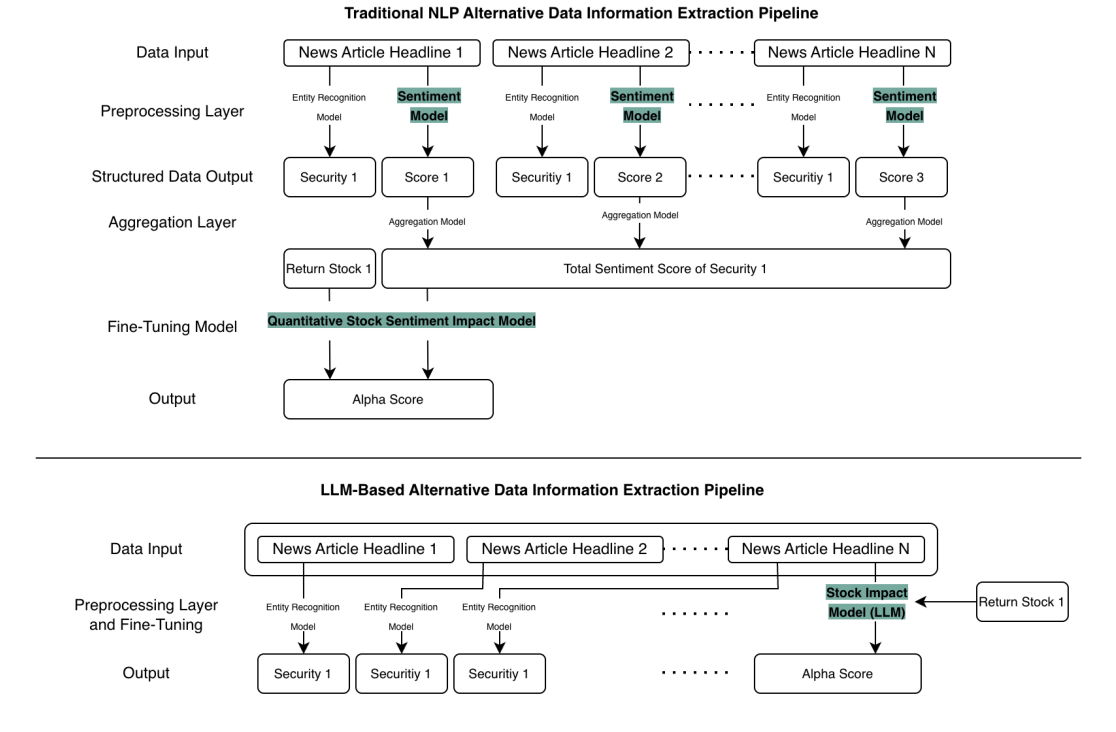

- LLM Quant: models extract signals from text and multimodal data, generate features, and interface directly with numerical pipelines. This marks a structural shift from dictionary-based sentiment (e.g. bag-of-words, lexicons, modular NLP pipelines) to more context-aware semantic extraction that maps unstructured text directly to economic impact. The traditional pipeline involves multiple discrete stages: entity recognition, sentiment scoring, aggregation across securities, and a separate fine-tuning model to produce alpha scores. The LLM-based pipeline collapses these into a more streamlined architecture where an LLM Stock Impact Model directly maps headlines to alpha scores, with entity recognition handled upstream.

- LLM Quantamental (AFI): scaling fundamental reasoning by converting analyst judgment, sector knowledge, macro narratives, and qualitative insight into structured datasets that quants can analyze systematically. This creates a bidirectional link where LLMs translate complex model outputs into natural-language explanations, and conversely convert qualitative insight into quantifiable signals. This has the effect of creating a new class of expert-derived alternative data.

The paper situates current adoption within a hype cycle: pre-ChatGPT encoder-based models (2018-2022), innovation trigger (2022), rapid expansion (2023-2024), trough of disillusionment (2024), and selective integration (2025 onward).

Before generative LLMs, quant researchers used encoder-based architectures like BERT, RoBERTa, ELECTRA, DeBERTa, and finance-specific variants (FinBERT fine-tuned on the Financial PhraseBank dataset, FinBART) for sentiment classification and named-entity recognition. These were deterministic, classification-oriented models suited for task-specific NLP and helped establish transformers as the baseline for financial text analysis. In parallel, transformer architectures influenced time-series forecasting through models like the temporal fusion transformer and informer. The shift to generative LLMs introduces context-aware language understanding, richer semantic extraction, and end-to-end impact modeling. Newer reasoning models (Claude 3.7 Sonnet, DeepSeek R1, Gemini 2.5) extend this with structured, step-by-step problem solving for code generation and statistical reasoning.

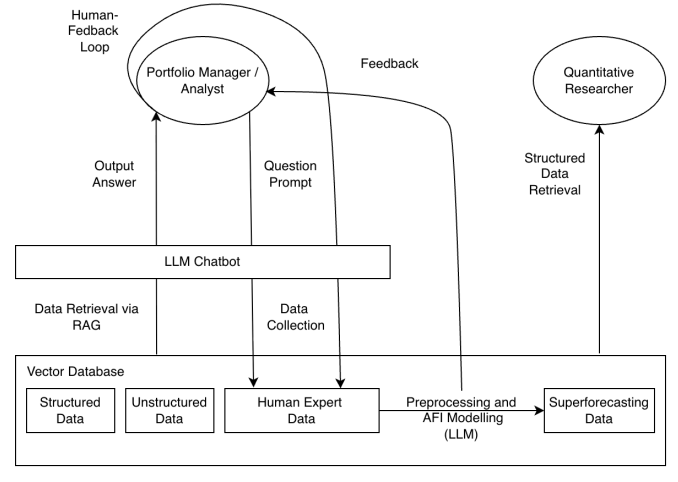

Two key infrastructure developments: RAG (retrieval-augmented generation) has become the standard for grounding LLMs in proprietary financial data, reducing hallucinations, and enabling real-time information integration via vector DBs. This connects portfolio managers and analysts to an LLM chatbot through a human feedback loop, with the chatbot retrieving from a vector DBs containing structured data, unstructured data, and human expert data. A preprocessing and artifical financial intellience (AFI) modeling layer (aggregates risk intelligence and data from protcols) generates superforecasting data that researchers can query directly.

Also, agentic workflows let agents run scripts, query data, and produce draft research (data preparation, backtesting, documentation) while keeping humans in control. Deep research is also heavily used due to the tooling to enable models to read and connect information across large volumes of filings, transcripts, reports, and academic research.

However, there are a few challenges specific to quantitative finance:

- Temporal leakage: LLMs trained on post-event data contaminate backtests; model knowledge cut-offs create forward-looking bias. Testing requires shifting dates, using artificial cut-offs, and checking whether anonymized inputs still produce event- or firm-specific predictions.

- Hallucination: particularly dangerous for financial claims where confident-sounding but fabricated facts can propagate into research.

- Memorization artifacts: models may reconstruct firm names, dates, and identifiers from training data. Testing involves masking identifiers and adding small perturbations (e.g., least significant digit changes) to detect reliance on memorized values.

- Behavioral biases: models display systematic preferences for certain sectors (e.g., technology) or size categories (large-cap), contrarian/momentum biases, and confirmation bias (failing to update beliefs when presented conflicting evidence). Also, foreign/cross-border bias where models show systematic optimism or pessimism linked to asymmetric information availability across geographic regions.

A few, more reconcilable issues include

- Numerical fragility: LLMs fail at basic arithmetic, ratio computation, and accounting identity checks (e.g., line-item tallies). Performance often depends on external tools (code interpreters), indicating weak native numerical reasoning.

- Reproducibility: API models update silently, breaking research pipelines. Identical queries may yield different outputs across time; for reproducibility-critical work, local fixed-weight open-source models are preferable.

In terms of decision making, an LLM is most appropriate when it delivers substantial, demonstrable out-of-sample improvements with no evidence of temporal leakage, memorization artifacts, systematic bias, or numerical fragility (among other challenges mentioned above). For deterministic tasks (sentiment classification, tabular prediction, accounting-based signals), simpler task-specific models like FinBERT, RoBERTa classifiers, or GBDTs remain more reliable.

Overall, LLMs are not reliable (yet) standalone forecasting tools. They enhance signal extraction, shorten research cycles, and improve interpretability of modeling outputs, but as complementary cognitive tools that extend analytical capacity while preserving expert judgment.

6: why reasoning models loop

From MIT and Microsoft Research, this paper investigates why reasoning models loop at low temperatures, identifying two mechanisms:

- risk aversion due to hardness of learning: when the correct progress-making action is hard to learn but an easy cyclic action is available, the model weights the latter more, causing looping at low temperatures.

- inductive bias for temporally correlated errors: transformers show an inductive bias towards looping because small estimation errors at decision points are correlated over time; when a similar decision point reappears, the model tends to reselect the previously favored actions, and under greedy decoding these errors amplify into loops.

Using Qwen, Openthinker3, Phi-4, and Llama, they sample 20 responses for temperatures $\in {0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0}$ on AIME 2024 and 2025, detecting looping via repeated $n$-grams appearing at least $k$ times ($n=30$, $k=20$ for reasoning models, $k=10$ for instruct). Key observations:

- all models loop at low temperatures; at temperature 0, Distill-1.5B looped 76% of the time.

- within a family, smaller models loop more; Distill-7B looped 49% and Distill-32B looped 37%.

- for distillation, students loop far more than teachers, pointing to imperfect learning as a key cause.

- harder AIME problems elicit more looping; they conjecture that for any model size, problems hard enough to induce looping exist.

- reasoning models loop when their instruct counterparts barely do, and RL training (Phi-4-Reasoning to Phi-4-Reasoning-Plus) doesn’t significantly reduce looping.

To understand the mechanisms, they introduce a synthetic task using star graphs $G(k,d)$: a root node connected to $k$ children, each leading to a chain of $d$ nodes ending in a leaf. One child is the goal path. The teacher generates random walks where the model navigates from start to root, picks children, and either progresses toward leaves or backtracks. The start-root-start cycle is “looping” and reaching the goal leaf is “progress.”

For the risk aversion mechanism, they study $G(k,d)$ where distinguishing the goal child from non-goal children requires learning a hard mapping (children are labeled with random tokens, so the model must memorize which token corresponds to the goal). The model learns the easy “reset to start” action well but struggles with the hard “pick the goal child” action. Proposition 1 formalizes this: if an action $a^*$ is indistinguishable from $m$ alternatives due to learning difficulty, its learned probability diffuses across all $m+1$ options (roughly $1/(m+1)$ each), while the easy cyclic action retains its full mass. The result: at low temperature, the model repeatedly resets instead of making progress because the cyclic action has higher probability than any single progress-making action.

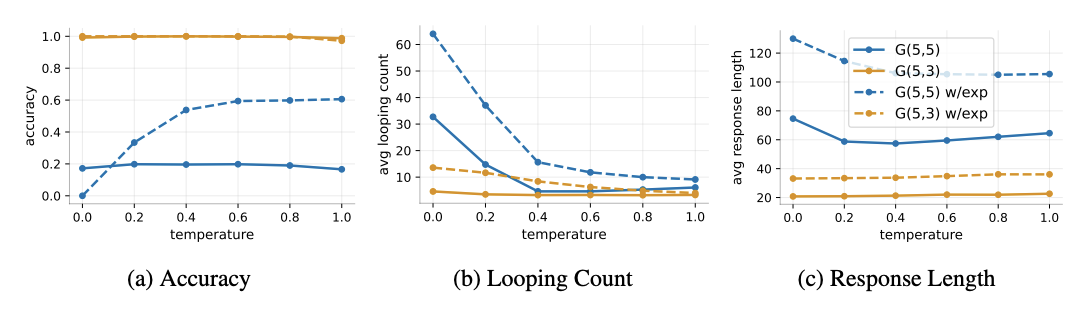

They test two variants on $G(5,5)$: (1) with exploration, where the teacher sometimes explores non-goal paths, and (2) without exploration, where the teacher always picks the goal child. In both cases, low-temperature accuracy is poor (~20% without, ~35% with exploration at temperature 0). Increasing temperature to 1.0 improves accuracy (to ~55% and ~85%), but response lengths remain 2-3x longer than a perfect learner’s. The shallower $G(5,3)$ graphs (orange) show near-perfect accuracy across all temperatures, confirming that the risk aversion mechanism is tied to problem difficulty.

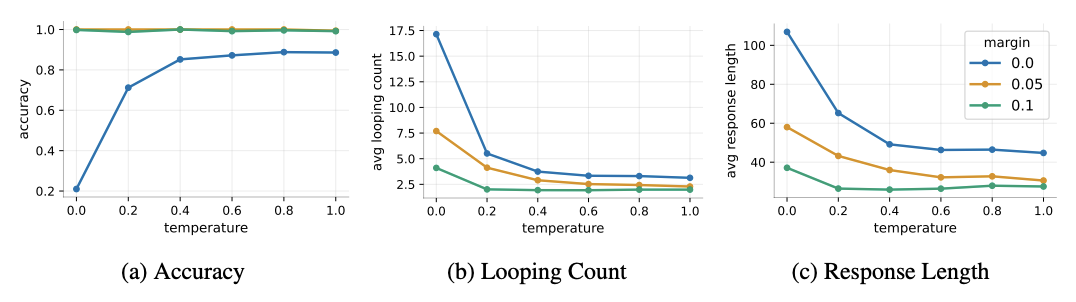

For the temporally correlated errors mechanism, they remove the hardness: all children are now easy to distinguish via unique tokens, but the teacher places equal (or near-equal) probability on multiple children at the root. Small estimation errors tilt the model toward a few options, and critically, these errors are correlated across time. When the model revisits the root after exploring a non-goal path and backtracking, it tends to pick the same children again rather than trying new ones. Under greedy decoding, these small correlated errors compound into loops. They test with margin 0 (uniform over all $k$ children), margin 0.05, and margin 0.1 (goal child gets higher probability). Even small margins dramatically reduce looping and response length because they break the symmetry, but at margin 0 the model achieves only ~20% accuracy at temperature 0 despite near-perfect accuracy being achievable.

A key finding is confidence buildup during looping: once a loop begins, the model becomes increasingly confident in continuing it. Plotting the maximum next-token probability over decoding steps shows that after the loop starts, the top-1 probability steadily rises toward 1, making loops self-reinforcing and progressively harder to escape.

Temperature reduces looping by promoting exploration, but it does not fix the underlying errors in learning. At higher temperatures, student models like OpenThinker-3 still produce substantially longer chains than their teachers (QwQ-32B), indicating that temperature is a stopgap rather than a holistic solution. The authors discuss training-time interventions (unlike-likelihood training, contrastive methods for isotropic representations, data-centric approaches) and raise a fundamental question: is randomness actually necessary for good reasoning, or does looping stem entirely from learning errors? The evidence suggests the latter; ideally, temperature would control exploration depth, not be required just to avoid degenerate output.